Journey on the Cowlitz

Words by Dameon Pesanti

Images by Pete Caster

Beginning in late May 2015, Chronicle reporter Dameon Pesanti and Visuals Editor Pete Caster began a three week journey down the Cowlitz River, a tributary of the Columbia River in Southwest Washington. The project took the two journalists from the air above Mount Rainier all the way to the confluence of the Cowlitz River with the Columbia River in Longview, Wash. To see the project in its entirety at http://cowlitz.seesouthwestwa.com/

In this aerial photo taken on Thursday, May 28, 2015, Mount Rainier looms to the north as the Cowlitz River winds its way through Randle, Wash. and the Cowlitz River Valley.

Through the Air

May 21 and May 28, 2015

By Dameon Pesanti

dpesanti@chronline.com

From about 1,500 feet up, the cities of Lewis County look like toy villages built into the threadbare patches of an old scrunched-up shag rug. Descend any lower and humanity’s imprint becomes more real and you see how we’ve imposed a geometric order over the natural world. Trees, like green starburst sentinels, stand in checkerboard formations, often abutting sprawling green fields or housing developments at the edge of town.

Climb higher and the cities begin to lose their character to become gray and black webs floating in a choppy green sea.

Soon, the curve of the Earth becomes apparent and all metaphors are lost when Mount Rainier comes into view.

In preparation for a two-week float down the Cowlitz River, The Chronicle took two exploratory flights over the waterway, from where it pours into the Columbia River up to its glacial origins in the Southern Cascades.

Our pilot was Dave Neiser, a former deputy with the Lewis County Sheriff’s Office who spent the majority of his nearly 40-year career flying over the county looking for illegal marijuana grow operations.

He retired in 2009, and the state legalized pot just three years later.

Now, he enjoys his retirement exploring the Pacific Northwest with his wife in his 1972 Cessna Cardinal.

When the weather broke, Visuals Editor Pete Caster and I met Neiser at the Chehalis-Centralia Airport for our first flight. I’m a pretty experienced rafter, but if we are going to float down this entire river, I needed to be above it and see what obstacles (aside from three dams) might be standing in our way.

On the first flight, the weather stopped us from going too far up river. Huge stacking clouds loomed in East Lewis County and none of us wanted to risk flying into a lightning storm. Instead, we flew near Mossyrock Dam and then followed the river until it met with the Columbia at Longview.

I’ve never been the type to get motion sickness, but I didn’t anticipate our pilot’s ability to maneuver his plane like he was the Red Baron. But with every mile my lunch stayed down and my spirit soared as I saw the world below us. From the tree farms and ranches, to the mills and ports, it was obvious how humanity has benefitted from living along such a waterway.

The river is long, mostly lazy, and cuts through a mostly bucolic landscape, but that’s only what I saw on the lower section.

I couldn’t make it for the second, and arguably most important, flight to the upper section of the river up into Mount Rainier National Park. Aside from some of the state’s best kayakers in the uppermost headwaters, few people float the Cowlitz above Salkum, so there isn’t much information in the rafting community.

Fortunately for us, Caster mounted a camera to the plane and recorded the entire river. For this journey to be successful, I need to know how choked the Cowlitz is.

I have a lot of footage to watch.

Day 1: Glacial Views? The Picture Is Fuzzy

Heavy Clouds and Friendly Scientists Greet Cowlitz Explorers

June 2, 2015

By Dameon Pesanti

dpesanti@chronline.com

Not everything goes as planned, and sometimes that’s for the better.

Visuals Editor Pete Caster and I drove to Mount Rainier National Park early Tuesday morning hoping to see the glacial origins of the Cowlitz River firsthand.

We arranged to meet with a couple scientists working in the park and hike to a spectacular vista of the Cowlitz and Ingraham glaciers — after all what better way to interview someone about a glacier than to actually have said glacier in the backdrop — but the weather had other ideas.

Cold heavy clouds blanketed the mountains and had no intention of coming off. While we planned on a scenic vista, we settled for a government conference room.

Perhaps it’s all for the better.

The hike to the 7,000-foot-high Cowlitz Rocks would have taken most of the chilly day and brought us through the snow. That would have been fine, probably even fun, had I been dressed for it. I might be slipping in my old age, or this (mostly) desk job is reigning in my wilder side, but I left the house bound for the largest mountain in the lower 48 states dressed in a collared shirt, a stylish jacket and the thinnest running shoes I own.

I didn’t realize how stupid my ensemble actually was until we were less than an hour away from the park and I thought to myself, “Man, it’s kind of cold today.”

Weather permitting, a mix of pride and a foolish commitment to my craft would have forced me up to those damn rocks. After all, what’s a couple frostbitten feet in the name of a good backdrop? Toes grow back … right?

If the gods were looking down on me, they probably didn’t smile, but instead rolled their eyes at my foolhardy ways and blew in the clouds to spare Pete from dragging my frostbitten self out of the bush.

So we didn’t get the headwaters for the photos, but we still had an interesting time.

Paul Kennard, a regional geomorphologist working at Mount Rainier, and his intern, Nick Hage, led us up the mountain for a first-hand explanation for how the warming climate has caused the glaciers to recede and thus dramatically alter the landscape.

At one point the Nisqually Glacier extended down far into the valley and the bridge crossing it was much lower than the one there today. Back then, some cheeky genius thought opening an ice cream stand next to a glacier was a solid business model for a national park roadside attraction. For reasons unknown, the ice cream stand didn’t survive, but the old bridge and road were washed away.

We headed for the Glacier Vista near Paradise, which would have put us right up to the glacier, but, again, the weather foiled our plans. The fog (clouds) was so thick that we wouldn’t have been able to see our feet, and that opens up a real possibility for vertigo, Kennard told us.

We settled for the Nisqually Vista, which offers spectacular, if distant, glacial views, but we were greeted by a wall of clouds. None of us were disappointed. Though socked in, the area had an eerie sort of beauty. The fog put kind of a solemn hush over everything.

Today, we’ll go lower and explore the twisting Box Canyon to see what secrets that secluded section of Rainier is hiding.

This time I’ll dress for the weather.

On Friday, it’s time to jump in the raft and head west.

Day 2: The Wild Roots of the Cowlitz River

Once More into the Tributaries

June 4, 2015

By Dameon Pesanti / dpesanti@chronline.com

As much as I’d love to hike to the Cowlitz Glacier, or as close to it as possible, time (and probably physical fitness) is not on our side. As a compromise, Pete and I explored the headwaters in and outside of Mount Rainier National Park.

Our first stop was the Ohanapecosh River just outside of the park boundary. I don’t think I could have prepared my brain for what we were about to see: a deep, mossy, stone canyon cradling a crystal clear river. There are several tight rapids and steep drops on the Ohana, making it off-limits to all but the most advanced kayakers.

It cuts through a mountain of bedrock and meanders around hundreds of boulders along its way to the Big Bottom. There was no soil to be had near the river; the riparian plants had only the moss and bit of hummus to thank for their lives.

I simply don’t possess the language to lasso such natural beauty without resorting to old cliches that have since been torn down and robbed of all their might. It’s a great tragedy that more people can’t feast their eyes on this place.

I had a fascinating conversation with a U.S. Geological Survey hydrologist this week. She told me the volcanic rock around this section of Rainier is some of the oldest in the entire region. At several points through history, glaciers filled nearly half of Lewis County — somewhere between 12,000 and 35,000 years ago, by the best estimates.

There’s no reason, she said, not to believe that the Muddy Fork of the Cowlitz didn’t create Box Canyon while the glaciers were still sitting above. Since the Ohana isn’t too far downstream, I presume it had much the same history. (Please, correct me if I’m wrong.)

While Pete was off shooting photos, I couldn’t help but stare into the waters and think of our paralleled histories. While water was presumingly just beginning to trickle down through the bedrock in this area, humanity in Eurasia had just finished the earliest known piece of human figurative art, domesticated dogs and invented needles and saws.

Humans came to North America 25,000 years ago. In half that time, we’d start domesticating sheep and goats. Ice would still be just outside Riffe Lake. Maybe I was caught in the moment, but in a way I felt we’ve made this journey through time together, these waters and us. Both progressing toward some great other beyond ourselves. For these waters it has been the sea, but for us it was new lands and ideas.

Now, thousands of years later, the Ohana continues its journey to the Pacific, wearing an ever deeper groove into the canyon, while we turn our eyes to space and dream of inhabiting new planets. Oh the things that come to mind after a few hours in the forest!

A few hours later we moved up the mountain toward Box Canyon, one of the least visited sides of the park. The Muddy Fork rages through the slot canyon there about 180 feet below the bridge. Despite the beautiful weather, only a trickle of tourists drove into the area. Unsurprisingly, they were all out on family vacations, and this was just one of several stops. As of this trip, one family from Tennessee had visited every state in America, save New Mexico. Regardless of where they were from, the sentiment was the same: This place is beautiful.

Today was our last visit to the park for this trip. Admittedly, I’m a little sad for it. There’s so much to see here, I have to come back soon.

Day 3: Oars Up, We’re in the River

June 5, 2015

A camper skips a stone into the Ohanapechosh River while hanging out on the morning of Friday, June 5, 2015 off of Forest Road 1270 east of Packwood.

For whatever reason, neither of us slept much last night. It wasn’t worry, at least on my end, that woke me up at 4 this morning. It was anticipation that kept me up.

After waiting for Pete to finagle the perfect shot of us before we left camp, we shoved off at about 9 a.m into the Ohanapecosh River, which eventually joins the Muddy Fork to create the Cowlitz River.

I wasn’t sure what was downstream, but I was transfixed by everything we came across.

The lower canyon is no less stunning than those closer to the National Park entrance. The rapids are only smaller. The bedrock walls cloistered the river into a narrow pinch and were covered by large cedars, rooted into whatever hospitable crack they, as seeds, were fortunate enough to fall into.

As pleasant as it was, the canyon was short-lived, and before we knew it, we found ourselves at the lip of the Big Bottom.

Just past the final wall, we drifted through the canyon’s end and met two 20-something guys off the shore. There are dozens of primitive grounds just off the beaten path in the Gifford Pinchot, and these guys were taking full advantage.

They were traveling up from the Oregon coast after finishing up seasonal jobs in Colorado. These next few weeks, they planned to spend a couple days exploring Mount Rainier while they’re between jobs. We chatted easily, as people in nature do, about other parts of the country we’ve seen and how gorgeous and strange their landscapes were.

After handshakes, we were off again and rolling downstream.

The Big Bottom awaited.

Here the river splits numerous times into a maze of braids and dead end channels. Navigating this was like running a maze where turning back wasn’t an option. We could hardly ever see what was around the bend until we were right upon the curse.

Still, most of the time, our guesses were correct and we avoided log jams and dead washouts. We did get stuck several times, but only twice did we have to get out, grab the ropes and hulk our craft over the stones.

Several times, the channels we chose were barely wide enough to fit the raft. Squeezing in both oars was nearly impossible.

Even into Big Bottom, the Ohanapecosh is as crystalline as water comes, a stark contrast to the slate gray slurry that is the Muddy Fork of the Cowlitz. Their confluence comes at a small bend just outside of Packwood, and from there on the Cowlitz itself is turned a luscious aqua blue. Now, sitting here outside the Skate Creek Road bridge in Packwood, that color has carried us downstream.

The world is an entirely different place from in the center of a river.

I think I drove Pete crazy by asking him at least a dozen times if we had passed Packwood. We saw several animals along the way.

There were at least two river otters lolling in the current ahead of us, though they were swifter than Pete’s draw for his camera. We also were graced with the presence of two eagles and a number of ducks. The avians seemed annoyed we were coming down the river, spiraling into the sky at the very sight of us.

Now into the main Cowlitz, the river is solid, albeit a bit lazy.

There’s a window of high water and, like Indiana Jones diving into the gap at the last second, we’re doing this float just before it closes. I was grateful for the rain earlier this week. It pushed the river up just a few inches, just enough, I’m guessing, to help us through. If we were to start this again, I think I would have started about a month earlier. Sure, the weather wouldn’t have been as ice, but the river would have been more swollen and the rapids more entertaining.

Here’s hoping for a wet summer and an even wetter winter.

Onward.

Day 4: Packwood to Cascade Peaks Campground

June 5, 2015

By Dameon Pesanti / dpesanti@chronline.com

Possibly the best element of a trip like this is falling into the rhythm of the natural world.

Sure, I’m still working just as hard — if not more so — as I do when I’m in my office back in Centralia, but the hours are more fluid and take on a different meaning.

Whether it’s self-created or an adaptation to someone else, I think there’s harmony lying below the surface. You wake up at this time, go to work at that building with these people, pick the kids up at this place, go to that store before it closes, pay your bills on this day, go to bed at that hour.

In my life, those behaviors are so far below the surface they’re practically automatic. But for these two weeks on the river, those routines have gone out the window and I’m left with the cycles of the sun and the tendencies of the river.

As I’ve said in other stories so far, we rowed hard from the morning well up to dusk on Friday after departing from La Wis Wis Campground along the Ohanapecosh River.

Part of the joy in exhaustively pushing myself through a long day’s work is savoring the flavors I otherwise wouldn’t give much thought to. Realistically, yesterday wasn’t so much about pushing as it was pulling — pulling our raft through the canyon, over rapids, around rocks, onto shore — but mostly down the lazy upper Cowlitz River by about 6 feet per stroke.

As far as rivers go this time of year, she’s a lazy, wide-mouthed stream, now that humans have anesthetized her fiery personality with three hefty concrete dams.

But that doesn’t mean she’s without risk or personality.

While most of the time the Cowlitz is slow to anger, all in Southwest Washington know her fury.

Each river has an attitude.

Any river rats worth their neoprene will tell you of the polite but antagonistic relationship we have with the water. A stiff current is always great when you’re seeking a little excitement, but can also be absolutely maddening when you need to slow down or get back up stream. Even the smallest currents can drive you nuts.

Ask anyone about their first few days at the oars.

I think of rafting and kayaking as dancing with a strong-willed partner. It’s best to understand right away that she will do whatever she darn-well pleases, and the best way for you to get what you want out of the engagement is to make your move around hers. If you don’t like it, then you can just prepare to die.

The outcome isn’t always that severe, but make no mistake: the river will always win.

If you’re too bold with her, she’ll pin your craft against a logjam with the force of all the water she can muster from upstream, or she’ll trap you in a recirculating hole from which escape is not guaranteed. Sadly, even those who do pay her the respect she commands still occasionally are found on the wrong side of the surface.

Washington state is full of angry waterways. Fortunately, for the purposes of our journey, the Cowlitz is a kind mistress — save the occasional snarl and snag.

We had every intention of stopping for camp around Packwood, but we couldn’t find a worthwhile spot. There was a god-awful wind blowing upriver. Every beach was a rock garden, and most of the forested sides looked like private land.

I’m a pretty charming guy, but I’m not sure I could talk my way out of a confrontation with an East County rancher who spotted two trespassers squatting on his place.

So on we rowed, and rowed, and rowed and rowed toward what we knew was a campground somewhere up ahead.

By the time we saw the RVs poking out of the trees near the U.S. Highway 12 bridge between Randle and Packwood, my back muscles were ready to slip off my spine. We stopped just upriver of a few campers and scrambled up the bank and through the brush to get to the property.

When an older woman sitting outside her camper spotted our rough mugs coming out of the trees, she turned to her companion and said, “Oh, look. Bush people.”

We found Jim Shepard, one of the employees of the Cascade Peaks Family Campground, and explained who we were and what we were doing. He lit up at the idea of our journey and offered us a free place to stay for the night.

Under typical circumstances, receiving gifts as a journalist is a huge no-no, but because this trip and this diary is not a typical pursuit of journalism, I felt in this instance it was acceptable.

As dusk settled in, I set to build a fire, but we didn’t have paper to start it. My trip companion and Chronicle Visuals Editor Pete Caster tried to use some moss, but it proved too damp to catch.

Here, dear reader, is where I give you a bit of knowledge.

Tortilla chips are excellent, if not the best, fire starters. I can’t speak to all chip varieties, but the grease left over from the creation fryers of those crisp, golden, triangles of deliciousness is enough to ignite, with the drop of a match, a flame that burns large and hot enough for even the thickest of kindling.

Even in spite of a fire, you don’t realize the vacuous dark of the night sky until you escape the city lights. As much as I wanted to savor it, after I got some food in my belly, it wasn’t long before I hit the sack.

Day 5: A Hot Sun and a Daunting Task

June 7, 2015

By Dameon Pesanti / dpesanti@chronline.com

As fun as this trip has been, it was hard leaving that campground. We floated from Cascade Peaks down to Randle. By car, you could make that drive in under 10 minutes. Take a raft down this slow and incredibly meandering section of the Cowlitz, and plan on spending about eight hours pulling at the oars.

For the first few miles, the river banks yawn wide, the current relaxes and gravel bars snake just a few inches below the surface before suddenly giving way to deep, turquoise channels.

Buzzards hovered in the breeze around us and occasionally flocked to the dead trees scattered along the shore. I didn’t know Washington had buzzards until recently, and I think they stared at me just as curiously as I stared at them. They’re oddly beautiful animals. Even in the wind, the scavengers glide easy on ebony wings, their red heads seemingly the only things that distinguishes them from ravens. A couple bald eagles combed the water, as did a number of low flying osprey.

At one gravel bar, we met a group of people standing around a couple quads and admiring the water. Ken and Karen Egger were over from Yakima, visiting their in-laws Don and Kathy Palen.

As soon as the good weather hits, the Palens leave their camper at the river and visit nearly every weekend. The Vancouver residents aren’t allowed to build a permanent structure on their property — it’s in the flood zone — but they make maximum use of their little slice of the Cowlitz Valley each year.

Ken Egger said it’s a welcome reprieve from the pace of life where he lives in Vancouver and owns and operates a mobile RV repair business.

They were all too happy to tell us stories and point us in the direction of a few elk upriver.

Our chance encounter with the group highlights what we have seen throughout the early portions of this journey — absolute, unfettered kindness.

Having exchanged names and information, we turned our raft west and again began the slow journey downriver.

At midday the current picked up, but the trees and submerged logs became so thick I almost thought the river had swallowed a forest. So far, no area has tested my oarsmanship as much as this one. The bossman himself, Chronicle Editor Eric Schwartz, joined us for this leg of the journey. He and Visuals Editor Pete Caster acted as lookouts for the many sunken lurkers that threatened to slice our floor in two. Heeding their warnings, I bobbed and spun from one side of the river to the other. More than once, we collectively held our breath as I missed some logs by only a few inches before spinning us back around to dodge another.

The trees begin to clear where the river twists into such tight serpentines that going around a bend almost feel like going backwards.

I spun the nose upstream and put my back into the oars. Eric and Pete sat on the tubes in front of me and paddled between my strokes. Despite our efforts, we moved at a little more than a crawl. If there was ever a time for chain gang work songs, something to imply finality to seemingly endless and futile work, this was it.

Salvation came in the form of a big steel and concrete bridge in the heart of Randle.

Burnt, dehydrated and exhausted, we scaled the sandy bank and headed for town. Maybe it was a trick of the brain or some vague hallucination, but I swear I heard angels at the sight of the Mount Adams Cafe.

With its classic diner feel and tasty American food, the place is a gem on U.S. Highway 12. The food was delicious, but I hardly had a chance to taste it because I ate so quickly. We chatted and swapped river stories with the owner, Don Lund. He, too, tried to float the Cowlitz years ago, but a nasty encounter with a logjam cut his trip short.

In a fortuitous twist, Lund offered to haul our raft across Riffe Lake in the coming days. Not looking to waste unnecessary time but still hoping to travel along the entire course of the river, his kind offer provides a compromise of sorts.

In one last gesture of the friendliness we absorbed from Packwood to Randle, he picked up our check, scrawling a note across the top.

“Thanks for not misquoting me,” it said.

Still hungry, and itching to write a bit later, I went across the street to the Big Bottom Bar & Grill, another Randle gem, for a mountain of curly fries, a glass of beer and a couple hours at the keyboard. After a game of pool, I was too tired for more than just a few sentences. So I crossed the highway and pitched my tent on a sandy bank of the Cowlitz River.

In the coming days, we’ll approach the three dams that give the Cowlitz River its form.

As daunting a task as this 105-mile journey seems, the events of the last few days have given us the mental fuel to move forward.

Day 6: Randle to Scanewa Is Hot, Flat, Beautiful and Tiresome

June 8, 2015

By Dameon Pesanti / dpesanti@chronline.com

Forgive me dear readers, for I have lied to you.

Although it wasn’t intentional, I sold you a bill of goods when I said Sunday’s trip was the most difficult. The truth is, Monday was the worst. Unless we end up having to row across Mayfield Lake, I can’t foresee any future days on this blessed journey becoming more difficult.

I wish I could tell you about how I physically prepared for this trip months in advance. I’d claim I passed the weeks before departure with a banner of the word “Cowlitz” high over my home gym as I exercised as if I were reenacting a Rocky movie, but alas, that would be a lie.

If it were on film, my exercise montage would definitely have “Eye of the Tiger” playing in the background, but instead of me jogging around Philadelphia and punching sides of beef, I’d be jogging to this tasty Indian restaurant just around the corner from The Chronicle’s office and shamelessly devouring massive quantities of food at the all you can eat buffet.

My cut scenes and B-roll would be a mix of my biceps flexing as I heaped huge piles of food onto my plate, my face froze in a sweaty grimace as I hauled the load back to my table, my jaw muscles clenching over and over, and the whole thing would end with a closeup of the buttons on my shirt stretching to their maximum.

I did go for a few intense bike rides from time to time. If you saw any of the photos or videos of me doing back flips off the raft these past few days, you should be as impressed as I am that my legs were able to get that belly of mine over my head.

With all that work I did, I’m still trying to figure out how it got there.

Visuals Editor Pete Caster and I started our day with two massive breakfasts, coffee and a bit of work at the Mount Adam’s Cafe in Randle, and we left feeling pretty good.

That all changed when we returned to our beach campsite below the Cowlitz River bridge. It was a million degrees outside, I swear. It was so hot that neither of us could do anything to put our camp away for about 15 minutes; we just stood there paralyzed by the blistering heat.

Once I did get moving, the sand burned my knees and the palms of my hands, and the surface of our rubber raft all but took off the first layer of our skin.

The heat made every minor detail a huge issue. A couple empty Gatorade bottles and a few plastic bags on the floor of our raft got me so annoyed with the perceived haphazard condition of our boat that I just started tossing things out and repacked it all over again.

As is almost always the case, life was better on the water.

It was still very hot, but I oared us under the shady overhanging trees for most of the float, which made a world of difference. The cerulean current carried along gently. Song birds called out at every bend. Calves and cows greeted us by the riverside, until we got too close and they scampered up the bank. A bald eagle taunted us by launching out of the trees, flying over the river and hiding somewhere in the timber ahead.

But about 2 miles after leaving Randle, the current slowed and then stopped entirely as the headwinds laughed upstream. Even with me putting my back into the oars and Pete paddling hard, we moved at a snail’s pace.

If we stopped, the raft stopped.

Either that, or it turned sideways and drifted a little upstream. It was this way for about 11 miles. We estimated our pace to be about 6 feet per stroke, a rate we figured would get us to Lake Scanewa sometime next month.

The seemingly endless flat water and mild sun exhaustion trapped me in a philosophical quandary that typically only comes up on late nights in a college dorm.

“When is a river a lake?” I wondered.

I mean, if it’s blocked by a dam, isn’t a river just a faster flowing part of the lake? Where is the defining line? How slow does it have to be before it’s considered lake water? Lakes have currents, why aren’t they rivers? What do the words “water” and “current” actually mean anyway?

Clearly, I’m not a scientist.

It wasn’t long before the evening set in. We hadn’t seen a person in miles. Our conversations slowed to a halt and the world was silent, save the rhythmic squeak and splash of my oars at work.

As we got deeper into the lake, the shore pulled away from us a little more with every stroke. At one point near a boggy spot of the lake, a splash broke the silence and Caster exclaimed he saw what he was sure was an otter.

Hoping for a photo, I oared as hard and quiet as I could toward the ripples.

Behind us, I saw another brown head flick the surface before diving again. We sat with bated breath, waiting. Then some grass rustled near the shore, sounding like something ran off. Feeling a little defeated, we rowed on, only to hear another splash upstream.

I spent more time on the phone than I care to admit. Back in cell service, I volleyed calls between my editor, Tacoma Power, the U.S. Geological Survey, Lewis County PUD and another reporter.

Somehow, Pete and I had to get ourselves around the Lewis County PUD’s Cowlitz Falls Dam at the west end of Lake Scanewa and meet with USGS for a story before 9 a.m. the next morning.

Later, we’d also have to meet with the dam operators for another package. With the newsroom on deadline Tuesday morning, a ride from Editor Eric Schwartz wasn’t an option, and PUD wouldn’t help us get our raft around the dam. Apparently, the Risk Management Department thought we were too much of a liability.

As usual, when we finally landed at about 8 p.m., Pete and I were exhausted.

Then things got complicated on the shores of Scanewa.

Initially, I improvised a plan for reporter Justyna Tomtas to pick us up where we camped at 8:30 the next morning. Then we’d all go to the dam and divide and conquer the stories.

But that didn’t solve our raft issue.

There’s only one boat launch on Scanewa, and it’s a busy one. We didn’t want to leave our rented raft and all of our other equipment tied up for three hours in such a busy location unattended. Plus, the grounds are covered with signs that say “day use only.”

I hiked around looking for a spot to camp, but thought better of it for fear of our stuff getting stolen.

We needed a better plan.

We called Justyna and had her come get us and the gear and the three of us checked into a hotel in Morton just after midnight.

It wasn’t an easy decision.

In fact, it was pretty frustrating, but we got the stories taken care of and the raft moved around the dam.

Still, it meant missing the Cispus River confluence and a little bit of the lake. Given our other responsibilities, it seemed like the correct call.

The Cispus and I aren’t done.

We’re pressing on for now, but I’ll be back before this series is finished.

Day 7: Far, Far From Glamping at Riffe

June 9, 2015

By Dameon Pesanti / dpesanti@chronline.com

Our Tuesday morning started with a trip up Riffe Lake to see how the U.S. Geological Survey measures water levels below the Cowlitz Falls Dam.

We rode with them deep into the canyon and were back onshore before 1 p.m. There was ample time for us to get on the oars and row out, but Don Lund, the owner of the Mount Adams Cafe in Randle, offered to give us a tow across the lake the next day.

Staring out at that 23 miles of choppy, windswept water, it was a ride neither of us wanted to miss.

For at least one day, we were stuck.

There’s a free camping area just before Taidnapam Park on Riffe Lake that we decided to stay at. It’s a known and popular spot for hang gliders and campers who aren’t willing to pay for the more developed campground down the road.

For the purposes of our trip, on Tuesday night the price was right and the view was great.

Unfortunately, it was the worst camping spot so far.

Evidence of human carelessness was everywhere.

Just off the road, there’s a big parking lot area and an outhouse surrounded by huge bags of garbage and glass bottles. Move down to the lake, and at several places you’ll see where people had ignored the “no vehicles” signs and driven off the road and through the marsh areas lining the water.

Down at the shore, there were tags from this and pieces of that poking out from the rocks. Without trees, there was no shade to escape the midday heat. Pete and I just set up our tents and did what we could to stay cool.

It wasn’t until after we broke camp that we realized there was a dirty diaper and several baby wipes sitting in our fire pit. Needless to say, we didn’t have a campfire.

I feel like you see peoples’ true sides in extreme, or at least abnormal, situations.

This campsite is a prime example. Of course, if you chide them and have a garbage can every couple feet, people will clean up after themselves, but left to their own devices, they’d much rather just leave their garbage everywhere than be inconvenienced with having to carry it out.

Shame on all who think it’s fine to leave garbage lying around.

Maybe the blame can’t be entirely on the litter bugs, because aside from the two outhouses and a few signs preaching responsible recreation, there were no dumpsters or facilities to speak of.

There were several other people camped near us and more than a dozen day-use types came and went, but none were all too friendly. One couple even parked their SUV about 10 feet away from our tents, stared at us for a few minutes, then set their lawn chairs on the other side of their vehicle. Maybe they thought we were traveling salesmen, religious fanatics, or saw our raft and thought we were pirates.

I’m not sure. Either way, none were interested in conversation, except for a couple ladies.

Near the evening, Kim LaFrance, of Mineral, and Dena Niemi, of Glenoma, came out to try their new paddle boards, but the wind and high waves put a stop to those plans. So, rather than get out on their boards, they watched the sun sink behind the hills.

“It’s not like it’s wasted time,” Niemi said.

In spite of it all, she was right.

USGS Measurements Help Inform on Cowlitz River Flows

On the River: Information Used for a Broad Array of Applications

COWLITZ RIVER — About a quarter of a mile below the Lewis County Public Utility District’s Cowlitz Falls Dam, three workers from the U.S. Geological Survey slowly comb from one side of Riffe Lake to the other, blanketing the water with sound.

The sound waves aren’t audible, but like sonar, they give the researchers a picture of what’s happening beneath them.

The red, white and blue acoustic Doppler current profiler (ADCP) is a little bigger than a coffee can and hangs vertically off the side of the boat and into the water.

It shoots sound waves about 13 feet down to the bottom of the lake. The waves interact with the particles floating in the water before bouncing back to the ADCP.

Ken Frasl, USGS field office chief for Western Washington, cruises the boat from one bank to the other several times so the machine can get a good reading.

USGS stream gauger Dan Restivo watches the measurements on a burly, waterproof laptop computer as they come onto the screen.

A thin smile of periwinkle and royal blue comes across the screen as it mimics the shape of the lake bed and informs the researchers where the particle flows are the most dense.

There are 10 sites along the Cowlitz River from just outside of Packwood down to Castle Rock. USGS visits the location just below the Cowlitz Falls Dam twice a year to verify the flows the dam operators believe they’re producing.

The Cowlitz is just one of roughly 400 gauging sites around Washington state where USGS measures streamflows.

When all the data is compiled, it creates a linear picture of how a river’s flow changes through the year.

The information is then used for a wide range of studies by the National Weather Service, the Army Corps of Engineers, private companies and many counties. It helps everything from flood warning systems to road and bridge construction.

The measurements are done around the state throughout the year, but USGS does them more often during extreme flows.

“It’s really important for us to get those extremes, otherwise we’re just guessing,” Restivo said.

At the Cowlitz, it’s important for the dam’s release to be at a certain flow so Tacoma Power can know how much water is coming into Riffe Lake, which is harnessed by its own dam.

For operators at Cowlitz Falls, the readings help ensure turbines are working properly, which ultimately helps them ensure a balance between the need for energy production and the health of fish populations into the year.

The delicate balance is made even trickier by drought.

“We had no snowpack this year,” Frasl said. “The lakes are full right now, but less water means less for power, for fish and for recreation, the whole thing.”

After several readings into the river particles, the machine reads the bottom of the lake to make sure it hasn’t moved around.

The dam operators estimated their water release to be 2,000 cubic feet per second, but the USGS machine read just over 2,300. The reading was higher, but not high enough to be of a concern.

“If we’re within a certain percentage, we go with what they have,” Frasl said. “More is typical, but it’s within reason.”

Day 8: Hang on and Stay Warm for Riffe Lake Haul

June 10, 2015

By Dameon Pesanti / dpesanti@chronline.com

Our ride was coming at 9 a.m. and we still weren’t packed, but we didn’t panic until they drove past with a friendly honk and wave on their way to the boat launch on the opposite side of Riffe Lake.

Not wanting to make the Lunds wait, we scrambled to throw everything into the waterproof bags and then into the raft.

What had been just days ago a neatly packed, highly organized excursion craft had morphed into a floating version of the Clampett family truck. But we got it out on the water and rowed into the waves with plenty of time to spare.

We met the couple in open water.

They had just recently purchased a handsome mid-80s boat named the Mer Sea and were taking it out for only the fourth time. Determined to say we were in our raft for as much of the Cowlitz as possible, we roped the raft to the Lunds and hung on for the ride. Because the raft has a soft rubber floor, neither of us could move around too much, Pete sat on one of the thorts and I perched myself on a tube.

For the next two-and-a-half hours, Pete and I bounced and splashed along behind at the mercy of the Mer Sea. Don pulled us at only about 8 knots, a pace comfortable and safe for all of our equipment, but just fast enough to be a challenge.

It kind of reminded me of trying to pin down a giant fish in really shallow water for about two and a half hours.

Nearly every wave was coming over the top and nailing us in the face while simultaneously hitting the tubes with enough force to make the whole raft bounce.

Although we weren’t doing any rowing, the ride was a lot of work. However, it was much better than the alternative. Riffe Lake is 23 miles long, and a brutal wind likes to blow east across it, kicking up sometimes 3-foot waves. In a boat, that would make for an uncomfortable afternoon, but in a raft, it would be nothing short of an exhaustive nightmare.

Without the help of the Lunds, I figure it would have easily taken us three days to get to the other side.

With about 20 minutes to go, Don called us up into the boat with them and we had some sandwiches and talked of life in East Lewis County.

I can’t thank the Lunds enough for their kindness, which mirrors much of what we encountered as we traveled from La Wis Wis Campground to Randle those first few days.

We landed at Mossyrock Park just short of 1 p.m. to find the place largely empty.

We set up camp and spent time talking to Tacoma Power, trying to organize a visit and shuttles around the dams.

You’ll see how successful we were in the coming days, as we prepare to cross Mayfield Lake before setting our raft in the direction of Longview and continuing our journey.

It’s still Columbia River or bust as far as we are concerned.

Electric: Tacoma Power Dams Produce Enough Energy to Power More Than 135,000 Homes

The city of Tacoma relies on hydroelectricity for more than half of its power supply. Of its four projects, none produce more electricity than those on the Cowlitz River.

The Mayfield and the Mossyrock dams produce enough power for more than 135,000 Pacific Northwest homes. The two dams work in synchronicity to ensure the right amounts of water are moving through the system to keep power production and water levels where they’re supposed to be.

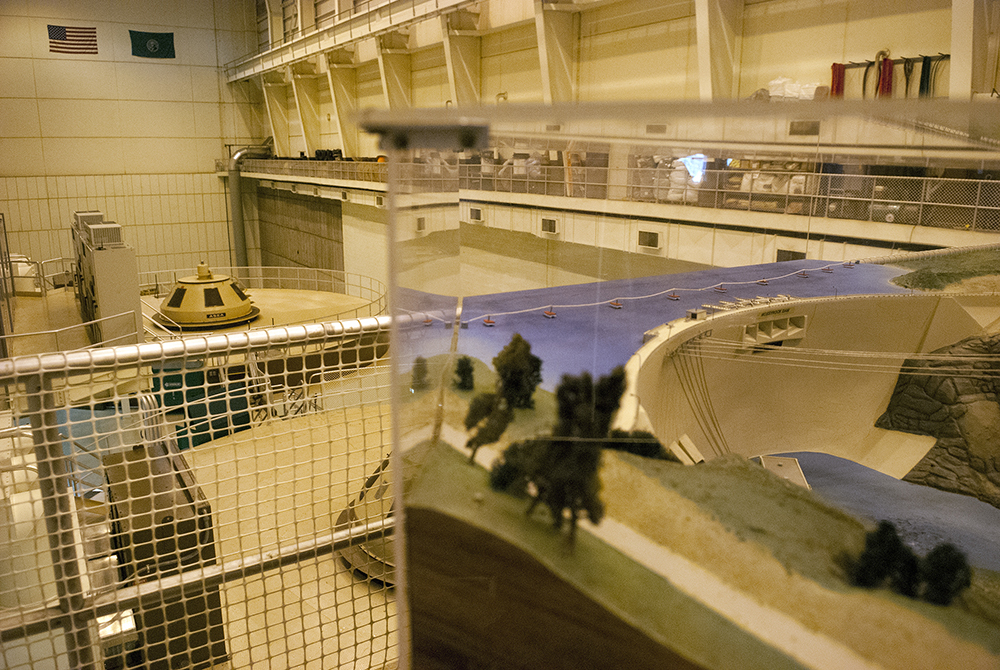

Over the last several years, Tacoma Power has been gradually updating several major elements of the Mossyrock Dam at the west end of Riffe Lake. Currently, a 300-ton crane is parked at the top of it where crews are working to remove the two headgates. Headgates control the water flowing through the dam and entering the turbine inside the powerhouse. Tacoma Power plans to remove and refurbish them one at a time, a move they hope will save ratepayers close to $1 million.

Tacoma Power generates about 40 percent of its energy needs from its four hydroelectric projects around the state, most of which comes from the Mossyrock and Mayfield dams.

The Mossyrock Dam creates the 23.5-mile-long Riffe Lake. While the dam’s primary function is for power production, it also plays an important role in flood prevention. For example, when the 2006 flood raised water levels to 25.2 feet in the Randle area, the Mossyrock dam held that water back in Riffe Lake.

“In 2006 they stored all of it,” Cowlitz River Assistant Project Manager Chad Chalmers

Inside the powerhouse, which sits at the base of the 606-foot-tall Mossyrock Dam, a loud hum of an enormous spinning turbine echos through the cavernous building.

In 2006, the city of Tacoma approved a $50 million project to replace much of the antiquated technology that had reached their lifespans. At several areas through the dam, equipment that has been online since the dam went into operation in 1968 sits in stark contrast to the modern counterparts that are replacing it.

Inside the control room, green panels with analog displays sit next to new gray ones that utilize a combination of digital and analog meters.

There are two turbines inside the powerhouse, both of which were replaced in 2010 and 2011, respectively.

Currently, only one of the dam’s turbines is in operation. The unseasonably dry winter and spring has put water flows at levels much lower than normal. It’s the kind of thing officials aren’t used to seeing until typically closer to early July.

“We’re running at about 3,000 cubic feet per second,” Cowlitz River Project Manager Larry Burnett said. “Normally, for this time of year, we’d be at 5,000. We could even drop to 2,500.”

There is room for one more turbine to be installed, but that’s not likely to happen anytime soon. The utility has considered adding another one, but with a contract to purchase power from the Bonneville Power Administration good until 2038, the cost is too prohibitive.

“Eventually it’ll happen. I’m guessing it’ll be after I’m retired.” Burnett said.

Day 9: A River Tamed, But With a Wild Spirit

June 11, 2015

By Dameon Pesanti / dpesanti@chronline.com

From Randle down, everything about the Cowlitz River changes.

At this point, the wild spirit of the river is broken by human ingenuity and yoked into obedience. Trees and pastures give way to lake houses, resorts, boat docks and a whole new kind of recreation for which a whitewater raft is ill-fitted.

Early Wednesday morning, we caught a ride from Riffe Lake around the Mossyrock Dam from Tacoma Power. Cowlitz River Project Manager Larry Burnett and Assistant Project Manager Chad Chalmers gave us a tour of the powerhouse at the bottom of the dam. Looking up at the 606-foot-tall behemoth, I thought of the James Bond movie “GoldenEye” and half expected Pierce Brosnan to come leaping off the top.

Tacoma Power was more than generous to the two of us.

Getting across and around Lake Scawena, Mossyrock and Mayfield was by far the most challenging part of this entire journey. Not only did Tacoma Power make time to show us the inside of their facilities, but they also sent employees Chad Taylor and Rick Hill with a trailer to move us around the Mossyrock Dam on Thursday and the Mayfield Dam on Friday.

I’m not sure how we would have done it without them, though at one point the idea of lowering us over the dam in a crane was mentioned (in jest I’m sure).

I’m very ambivalent about dams.

I recognize electricity as the cornerstone of modern life and all its benefits. As an environmentally conscious person, I much prefer hydropower to coal. But seeing the river choked reminds me that there’s no such thing as a free lunch. Blocking off the Cowlitz effectively halted salmon and steelhead runs that had been moving up stream for a millennia or more. It’s true that in recent years Tacoma Power has done well with their hatchery programs to restore some of what was lost, but nothing replaces Mother Nature.

As a boater, I can’t help but be sympathetic to the “never forget, always lament” kind of attitude held by the state’s kayaking and rafting communities about the 42 miles of white water rapids now sitting beneath the lakes. Whitewater types are like the spicy food lovers of the world. It’s a taste not commonly held, but the people that like it really like it and they’re disappointed when their tastes aren’t met.

For everyone else, the lakes and the surrounding parks and campgrounds created since the dams were installed have created a world of recreational opportunities much more accessible to the general public than a deep and narrow river canyon. Riffe and Mayfield are loaded with boats used by anglers, family vacationers and water skiers all enjoying the water, not to mention the dozens of businesses that have cropped up to cater to them, bringing much needed dollars to the east end of the county.

On Thursday, Tacoma Power’s Chad Taylor dropped us off at Ike Kinswa State Park. While loading up at the dock, we met Dan Barton, an Onalaska resident with a day off and a mind to slay some fish. Seeing that his battery was low and we were about to row across the lake, he gave us a tow. Not only did it save us work, but it charged his boat up enough for a day of trolling. With the wind still low, Pete and I rowed west until Dannie Richardson met us about midway. He volunteered to tow our raft back to his place, the Lake Mayfield Resort and Marina, and give us a place to stay for the night.

Richardson is a character as kind as he is entertaining.

A former helicopter pilot who in the military flew missions in Vietnam, then, as a civilian, flew professionally to remote locations around the world, Richardson divides his time between running a resort and fishing the lake in his new boat. He has a rare skill to tell stories of his world traveling experiences that are engaging without being braggadocios.

He took us deep into what remains of the Cowlitz canyon below the Mossyrock Dam, a world virtually unseen to those without a boat, and one I’ve been dying to visit since I moved to Lewis County.

Though I’d become jaded by our perceived return to civilization at the lakes, I was awestruck by what we found below the U.S. Highway 12 bridge. The water, which upstream ran with a turquoise hue, has been filtered by the dams and now looks like over-steeped green tea.

With a fish finder, you can see where the river channel snakes between underwater cliffs. Often in just a couple feet toward one bank or the other the depth goes from 12 feet to around 80 the entire way up to the dam. Gradually, the lake’s shores squeeze inwards and upwards and the banks reach high overhead. In this place, all traces of humanity are gone. Despite the prominence of the Highway 12 bridge, it makes only a short appearance before being lost behind the canyon walls. Life here thrives in green abundance as moss, ferns, wildflowers and trees cling to the cliffs and compete for the sunlight (see photos on pages Main 8-9). If brought to this place blindfolded, you’d be forgiven for thinking that this was a tributary deep in the Amazon.

“If this were the Blue Nile that’d be the perfect place for an alligator,” Richardson said as we cruised past the small coves that dot the gorge.

Bird songs filled the air. At one point, a great blue heron stood perched on a rock and warily watched us roll by.

“If he’s here you know there’s fish here,” Richardson said.

Within a couple miles of the dam, the current gently returns and licks tiny swirls past gentle upwellings. It begins to knock the boat around in rocky channels almost too narrow to turn back. Unexpectedly it all opens up again about a mile from the dam. There was still lots of water to explore, but Richardson’s responsibilities forced us to turn around.

We spent the afternoon on the flat, comfortable and grassy shores of the Lake Mayfield Resort. Sleeping on a leaky bedroll gives you a whole new appreciation for even ground. As nice and luxurious as these campgrounds are, I’m dying to return to the moving water.

We’ll do that when we return to the river early Monday morning after a brief return to civilization over the weekend.

We plan to reach Longview in the coming week.

Day 10: The Fishermen Smirk, While the River Relaxes

June 14, 2015

By Dameon Pesanti / dpesanti@chronline.com

It’s hard to ignore the pungent smell of dead fish at the Barrier Dam boat launch and even harder to escape it. For fishermen, it’s a sign of a promising hole. For three sleepy newspapermen, it’s good incentive to blow up the raft and get to better-smelling waters.

On Monday, Visuals Editor Pete Caster and I were joined by Sports Editor Aaron VanTuyl to kick off the final third of our journey down the Cowlitz River. We were greeted by grumpy fishermen, fellow adventurers and a number of beautiful homes.

In order to keep things as live as possible, we took the weekend off and started anew Monday morning. With the speed Pete and I have moved down the river, we would have finished this trip before today’s newspaper was printed. It felt like cheating, but sleeping in my own bed was a refreshing experience.

We also skipped the mile or so of water between Mayfield Dam and Barrier Dam. Rebuilding and breaking down the raft for such a short trip seemed like far too much effort for such little reward. And, while it’s true Barrier Dam is small enough to float a raft over, traversing a low head dam is a wholly stupid and extremely dangerous idea. They don’t call them “drowning machines” for nothing.

Everything about the Cowlitz changes below the Barrier Dam. The river’s spirit returns again, but it’s not the beast it is at the mountainous upper reaches. For better or worse, the metered discharges from the dams and reinforced banks are like fluvial Prozac; they do away with the river’s hostile behaviors and bring it down to manageable, predictable levels. Side effects may include swollen reservoirs, increased energy, unnaturally consistent flows and decimated fisheries. Talk to your power company for more information.

I don’t think I have to tell you about the number of fisherman that flock to barrier dam when the fish are running. Even on a Monday morning the place was full of anglers — most of whom weren’t very friendly, on this day at least.

At one point, we floated past three chubby guys in their late 50s fishing out of a drift boat who chuckled at us and made feeble cracks about “the dangerous falls” up around the next bend.

“We almost lost grandpa up there years ago,” one said.

While some fishermen could be obnoxious, there were none worse than the client-carrying fishing guide. This is not true of all, but some think they own the whole river — especially the prime fishing holes. It was nothing for them to scream upstream at full speed just a few feet away from us, but God forbid our non-motorized craft float within 30 feet of them when they’re floating in the center of the river with poles out.

I get it, it’s a service job and they’re out there to ensure customers have the best possible experience, but a little consideration!

Aside from us, the only other floaters out there today were a group of four people in a very stout drift boat. In the center was one man in a red life jacket pushing hard at the oars, treating his job like it were an exercise regimen, not a joy ride. Turns out, it was both.

They all declined to give their last names, but two couples — Jeff and Betsy and Miller and Sharon — were all in their mid-60s with a host of shared wilderness adventures under their belts. Monday they were warming up for a 211-mile excursion down one of the most famous and wild waterways in the West — Idaho’s Salmon River.

Their boat was a handsome silver and red aluminum drift boat, welded and reinforced into a white water basher named “Latikuf.”

When asked about the name, Jeff just laughs and says it was his midlife crisis boat and leaves it to you to figure out.

“When there’s kids around I tell people it’s an old Norwegian name with all of these special meanings,” said Betsy. “But it makes more sense to the dyslexic.”

The closer you get to Toledo the shallower the river becomes, but there’s always at least a few feet beneath you. The submerged forest groves of the east are non-existent, but a few trees have tumbled off the hills to spend their final days reaching out to the middle of the river. Dozens of homes, some of which resemble mountain chateaus, also start to appear along the banks. Occasionally we saw people lounging on their porches, sipping at drinks and gazing onto the water. Some didn’t notice us, but others offered full-arm hellos as we drifted by.

We completed the day in Toledo at about 1 p.m., much earlier than I anticipated, but still with plenty of time to file this report. Tomorrow we’ll head to Castle Rock to find what awaits us at the Toutle’s confluence.

Day 11 & 12: Soaring to the Finish: Journalists Finish Journey From Mount Rainier to the Columbia River

June 15, 2015